The Landlord's Lock

17 Feb 2026

NASA erased the first steps on the Moon. We erase the record of our own lives

On March 31, 2024, just before noon in Lyon, Étienne sat with the curtains half-drawn against a pale spring sun, trying to lose himself in America. Above his monitor, the shelf held quiet evidence of his offline life: a stack of concert tickets from 2011, a jar of sea glass, and a framed photograph of his parents from 1998, its colors softened by time.

For nearly a decade, his most vivid hours had unfolded in a place he couldn't touch. Ubisoft's racing game The Crew was a long, confident America built from postcard geography. He had a Koenigsegg Agera R there, tuned until even its smallest misbehavior felt familiar. The game had stopped feeling like a product and started feeling like a place.

At noon, the place shut him out. The screen froze. Étienne clicked “Retry,” a reflex born of years of minor glitches, but the loading spinner spun once, then stopped. The servers had gone dark. Months earlier, the company had announced the shutdown, citing “server infrastructure and licensing constraints” - a phrase that sounded less like a necessity than a lease expiring.

Later that day, Étienne opened his game library. The icon for The Crew, usually a vibrant blur, looked washed out; the “Play” button had been replaced by a grayed-out placeholder. He set the controller down and looked up at the photograph of his parents. The contrast was brutal: the photograph would go on fading for years under ordinary sunlight. The world on the screen had not faded. It had simply been revoked.

Étienne wasn’t a customer. Étienne was a tenant. And the landlord had just changed the locks. That evening, scrolling through Reddit, he realized he wasn’t alone. People weren’t describing a lost pastime; they were describing a lost place - roads shared with siblings, late-night routes that had become routine. The complaints read less like consumer anger and more like disorientation: the sensation of standing outside your own history, watching it remain intact and unreachable.

It is tempting to dismiss this as a story about video games. But The Crew is a clean demonstration of a much larger confusion: we keep using the language of ownership for systems built entirely around access. We have begun to store family memory the way we store electricity: invisibly, on demand, somewhere else. Photos, messages, calendars - the private texture of a marriage - everything that used to live in drawers now lives behind a login screen. And logins, it turns out, can’t be inherited. They are credentials: issued, updated, and withdrawn. We mistake storage for custody, until grief exposes what the cloud does poorly.

A few months after the shutdown, an unlikely figure turned that private frustration into a public accusation. Ross Scott is not a lawyer or a politician - less a visionary than a man coming off a three-day argument with copyright law. He is a YouTuber best known for his channel, “Accursed Farms.” In a video, recorded from a dim room, that galvanized the movement, Scott read an email from a seventy-year-old grandfather. For years, the man wrote, he and his grandson, who lived in another state, met every weekend in The Crew. It was their “third place,” a neutral ground where they could race cars and simply talk. When the servers went dark, the grandfather didn’t describe a lost product. He described a lost ritual.

Scott let the silence hang, then gave the loss a name: cultural vandalism. In the physical world, vandalism is obvious - spray paint on a mural, a smashed bench, a library book torn in half. In the digital one, it can arrive as a polite notice, a policy update, a button that grays out. The damage is the same: a shared place is destroyed by the person empowered to do so.

His demand was not for immortality. Keeping servers running forever is economically untenable. The demand was for a new compact: the right to self-rescue. If the building is closing, the landlord should be obligated to unlock the doors and let the tenants carry out whatever they can salvage.

The industry’s resistance came dressed in the language of security. Marcus, a veteran back-end engineer, rubs the bridge of his nose, not looking up from his monitor: “People think it's just one file. Like you grab game.exe, stick it on a flash drive, and you're done. But under the hood, it’s hell. You’ve got three layers of middleware, license servers, some ancient database that hasn’t been patched since 2015. It’s not software. It’s a house of cards held together by superglue. You pull one thread - you hand over the code - and everything crashes: auth, physics, the store. Plus, if I give you the server code, I’m basically gifting you an exploit for three of our other games. The lawyers would eat me alive.”

It is a valid defense. It is also a convenient one. In the physical world, there are regulations for condemned buildings. In the digital one, the owner can bulldoze the structure with the tenants still inside and call it maintenance. Advocates reply with an old-fashioned moral claim: if you invite people to build a life inside your digital walls, you owe them a path to an orderly exit.

Once you accept that framing, the grayed-out button on Étienne’s screen stops looking like a consumer complaint and starts looking like a dress rehearsal - one that ends with the option to erase. If a company can delete a grandfather’s “third place” with his grandson, it can delete the family album too: the photo library, the message history, the cloud drive - the digital archives you thought were simply “there,” until an administrative decision turns them into something ghostly: intact, and unreachable.

It was this imbalance that legislators in Sacramento eventually tried to address. By September 2024 - mere months after The Crew servers went dark - Governor Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 2426. The law did not ban the button; it forced the word "buy" to carry an asterisk. Starting in 2025, digital storefronts would be required to disclose that what you were buying was a revocable license, not a product.

***

A father named Mark discovered what eviction looks like online years before any legislator tried to regulate the vocabulary. The New York Times later reported it began with a routine precaution. In February 2021, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, his young son developed a painful groin infection. Mark wanted to avoid an emergency-room visit. So he did what telemedicine has quietly taught parents to do: he took a photo of the inflammation with his phone and sent it to the child's pediatrician.

The doctor prescribed antibiotics. The swelling subsided. The immediate crisis passed. Two days later, the phone still worked. The lights still came on. But the services linked to it no longer recognized him as a legitimate user. A notification informed Mark that his Google account had been disabled for a "severe violation." The medical photographs, the system told him, had been flagged as child sexual abuse material.

The lockout was comprehensive: email, contacts, documents - the scaffolding that holds a life in place - went with it. Mark assumed context would matter. He appealed. He gathered what evidence he could. He walked into a police station carrying a physical folder - doctor's notes, the photographs, the plain medical facts of what happened. The officers reviewed the material, confirmed that there had been no crime, and closed the case.

But Google did not reopen the account, saying its reviewers saw no visible rash or redness to justify the image. The system had also surfaced an older video: his four-month-old child, unclothed, playing in bed - an ordinary domestic scene that, in most families, would have been too mundane to think about until it was too late to retrieve.

Almost everyone who grew up with family albums in the seventies and eighties knows that kind of image: newborns with crinkled bodies and reddish skin, the awkward folds of a world that has only just begun. Sometimes the baby is in pajamas, sometimes not, because the point is not the outfit. The point is the record: the first minutes, the first proof that a person is here. When we turn those pages, we see vulnerability, trust, tenderness. A risk model sees something else: a probability score.

What Mark remembered as a cozy, lazy morning, the machine treated as evidence. "If only he'd slept in pajamas," Mark later said, "this all could have been avoided." The sentence carries the dark, involuntary absurdity of trauma: the sense that catastrophe has been routed, with perfect seriousness, through a detail so banal it feels like satire. In the cloud, the distance between a precious memory and a digital crime can narrow to a strip of fabric. To a father, it is life. To an algorithm, it's a flag. Mark was innocent in the eyes of the law. The machine had a different verdict.

***

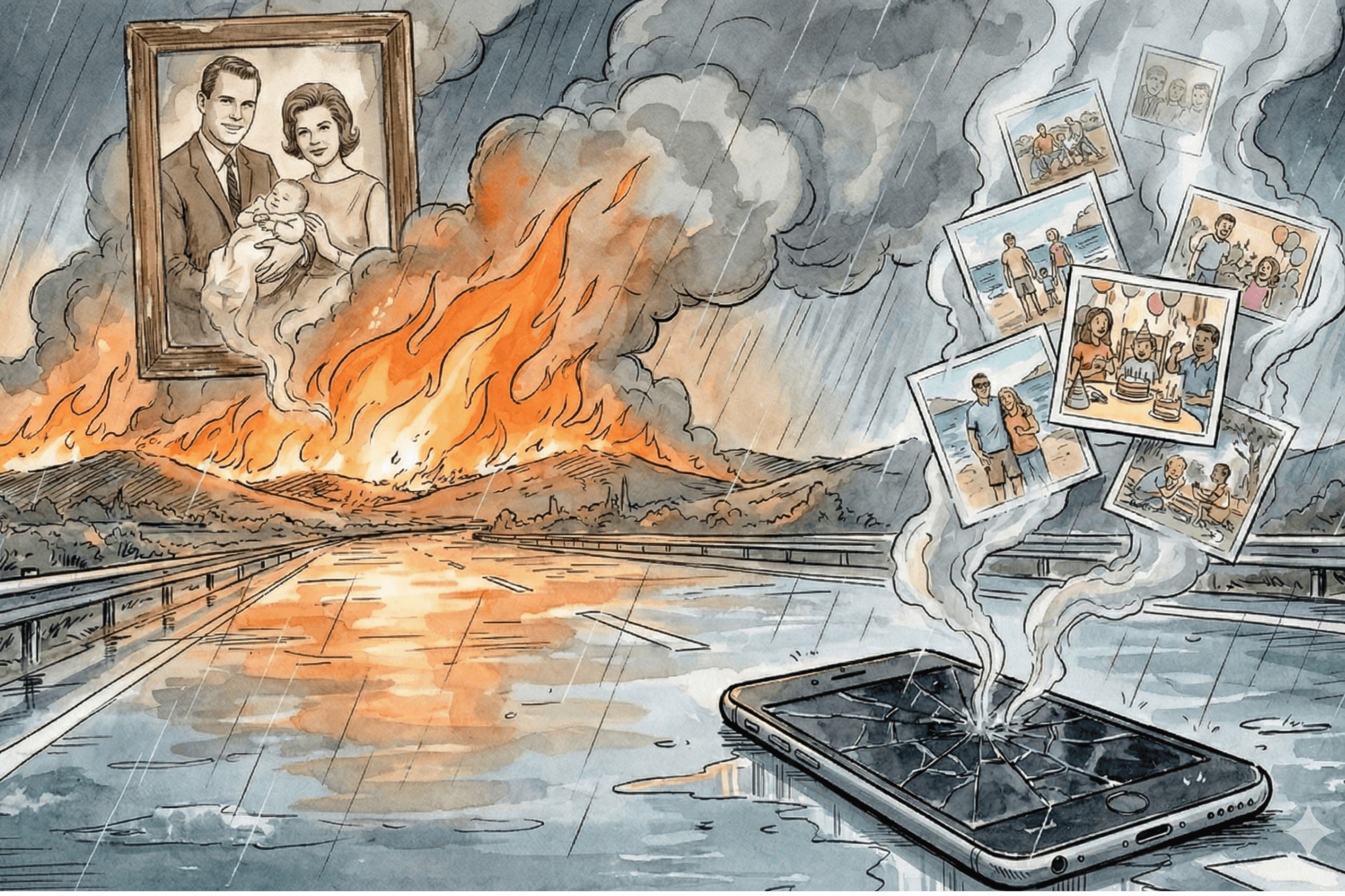

If the digital world is defined by silent erasures, the physical world still ends with a roar. On the evening of January 7, 2025, the Eaton Fire ignited near Eaton Canyon in the San Gabriel Mountains. Driven by Santa Ana winds, it pushed toward the foothill communities of Altadena and Pasadena with a speed that made "disaster preparedness" feel like a cruel abstraction. Life contracted into minutes: a narrow, irrational window in which you decide what you are willing - and unwilling - to lose.

Sarah, a graphic designer who lived near the foothills, made what she would later call the rational choice. She stood at the mantelpiece and looked at the photo albums aligned there like a domestic archive. Then she did the small, brutal math of evacuation: the albums would be 7 kilograms in her arms; the cat carrier was a kilo and a half. She took the carrier.

The heaviest one had a leather spine labeled in her deceased mother's handwriting: Little Sarah. The lettering had the slightly uneven pressure of a hand that took time for granted. Inside, on the back of the very first snapshot - Sarah, newly arrived, held in her parents' arms in the house that would become the backdrop of her childhood - there was a note in blue ballpoint: "Sarah, you will never remember this moment, but we shall never forget it. March 21, 1967, 12:44." The sentence did what old handwriting often does: it made the past feel oddly present, as if the ink had preserved the temperature of the room.

From the freeway, watching smoke build over the neighborhoods, she felt a strange, guilty calm. Four years earlier, she had digitized the albums, meticulously adding dates and names to every file. Her house - the one she was carried into as a baby - might burn, but her memories were safe in iCloud - somewhere inland, somewhere indifferent. She had, without quite admitting it, handed the fear of losing them over to iCloud, as if dread could be stored offsite with the files and retrieved only when she was ready to feel it. Sarah believed the cloud was a spirit. The cloud is not a spirit; it is a tether. And for the tether to hold, it has to be secured at both ends.

Five miles away, inside the gymnasium of a high school that had been turned into an evacuation center, David sat on a folding chair that squeaked every time he shifted his weight. Trying not to wake the family sleeping next to him, he discovered what that sentence meant in practice. The air was thick - floor wax, nervous sweat, the sharp stink of woodsmoke clinging to synthetic fabrics. His hands were shaking, not from the cold but from the suddenness of a new problem: the need to prove, to a machine, his right to his own account.

Unlike Sarah, David had fled with almost nothing. In the panic of evacuation - wind, sirens, the sudden violence of embers - he dropped his phone in the driveway. He didn't stop to look for it. He got his children into the car and drove. Now, safe but severed, he was trying to log into his Apple ID from a borrowed laptop to retrieve insurance documents. He typed his email. He typed his password - his fingers remembered the pattern. The screen refreshed.

A prompt appeared - minimalist, non-negotiable: Enter the verification code sent to your trusted device. The code had been sent to the phone that was, at that moment, melting on his driveway in Altadena.

David clicked "I didn't receive a code." The system offered another option: a recovery key. David remembered generating it a year earlier, doing the responsible thing security articles recommend. It was printed on a sheet of paper in the bottom drawer of his desk - the same desk that, for all he knew, was already ash. To the system, David without his phone was indistinguishable from a stranger on the other side of the world. He knew his password. He knew who he was. But he was up against a machine trained, by design, to ignore him. In the eyes of a security architect, David's predicament is not a failure. It is the point.

"Look, I get it. It’s a sob story," says Alim, a cybersecurity consultant who designs authentication flows for banking apps. “Genuinely sad. But from a SecOps perspective? That’s just a vector. Any 'panic button' is a vulnerability. You slap a 'Break Glass in Case of Fire' sticker on it, but a hacker just sees a sign that says 'Walk Right In.' Give me twenty minutes and a spoofed number, and I’ll walk through that door before you finish your coffee." He shrugs. "You can’t code for empathy. Code doesn’t know how to pity. It only knows how to follow instructions."

The logic is ruthless but mathematically sound. It is statistically safer to lock out a legitimate user like David than to admit even one attacker. "If we added a 'panic button' - a way to bypass 2FA during an emergency - hackers would exploit it within twenty-four hours," Alim told me. "You can't code for empathy without creating a backdoor."

David sat back in the folding chair, surrounded by the noise of displaced strangers. He was a refugee twice: once from fire, once from code. Three days later, he was still in the gymnasium. He had borrowed phones, tried recovery options, called support lines. Each path looped back to the same demand: produce the device you no longer have. Then a neighbor found them in the crowd and showed them drone footage on his phone. David's house was still standing. The walls were scorched, but the structure held. His desk was intact. The recovery key was in the drawer exactly where he'd left it - waiting for him behind a door he could not yet open.

In that moment, David understood what the marketing of "eternal memory" leaves out. In the architecture of the cloud, proximity means nothing. Your past can be sitting in a drawer fifteen miles away and still be as unreachable as if it were on Mars. Sarah's calm, too, was built on a misunderstanding. She believed her memories were safe because they weren't in her house. She forgot that they still had to live in someone's house. And houses - digital or physical - share one flaw. They can burn.

***

On the evening of September 26, 2025, in Daejeon, South Korea, the government data center underpinning a great deal of modern life caught fire. It wasn’t supposed to be the kind of place that burns - just as the Titanic wasn’t supposed to be the kind of ship that sinks.

“Let’s be honest,” says a site reliability engineer who works for one of the world’s largest cloud providers. “The cloud is vastly more reliable than anything you could build in your basement. We’ve solved for the physics of failure.”

And yet even the best-run systems carry a quiet, human-sized flaw: a gap. The interval between “we received your file” and “it has been durably copied somewhere else.” In many architectures, that window is roughly five minutes - long enough for a photograph to exist in only one place, still in transit to safety, still dependent on the room it happens to be sitting in.

Translate five minutes into human terms. Facebook once reported roughly 350 million photo uploads a day - about 1.2 million photos in five minutes. Snapchat has reported more than four billion Snaps a day - about 14 million photos and videos in five minutes. That’s nearly 15 million pieces of media on two platforms alone. Add YouTube uploads and the rest of the social internet, and a conservative conclusion is simple: in any five-minute gap, there are more than twenty million new photos and videos moving through the world’s clouds. In statistical terms, it is almost nothing - about 0.01% of the whole, the newest sliver that can actually be lost. For you - if one of those files is yours - it’s the whole story.

And in a crisis, that gap stops being theoretical. At six p.m. that evening, a systems administrator named Park was settling into the control room at the National Information Resources Service. On his desk, next to a bank of monitors cycling through green status lights, stood a framed photograph. It captured the day his daughter graduated, but more importantly, it captured the audience: the Park clan gathered in one room, the kind of assembly that happens less and less as the years peel people away. On the back of the print, aunts and cousins had signed their names - the dead and the living sharing the same square of paper.

Park was so fiercely proud of the girl that he had brought the frame to work that morning to use the department’s high-resolution scanner. He uploaded the digital master copy to the government’s G-Drive system just before his shift began, texting his parents with the confidence of a convert: “It’s safer there. The government’s cloud never goes down.”

Downstairs, contractors were doing something that also sounded like safety: moving aging lithium-ion battery packs for replacement. Batteries in data centers fail the way people sometimes do - quietly, until they don’t. The plan was risk reduction. It also introduced a new kind of risk: handling.

At 8:20 p.m., Park’s phone buzzed. A camera feed flashed on one of the monitors from the battery room. The image flared into a hard, white bloom - too bright to be information. A battery had ignited. Within minutes, thermal runaway began: a technology meant to prevent a power crisis had started one. The air turned hostile - extreme heat, smoke that made breathing a negotiation, fire moving faster than the mind wants to accept.

By morning, the blaze was under control, but the work did not feel like victory. Hundreds of servers were shut down to prevent further damage. For a while, South Korea discovered what it feels like when the machinery of ordinary life stops answering - when portals and IDs and databases become, all at once, a room full of locked drawers.

In the days that followed, as the smoke cleared, the more unsettling story emerged. The country didn’t “lose the cloud.” It lost a building. And the building contained a system that many people had been instructed to treat as if buildings no longer mattered.

One platform kept getting singled out: G-Drive, the internal “Government Drive” used by civil servants as a mandated home for work documents. Officials said there was no backup for it; the volume was too large.

The phrase sounds like bureaucratic fatalism, but it is really a budget decision. “Too large” means “too expensive to duplicate.”

“People assume the cloud is magic,” the engineer says. “But real-time mirroring - active-active redundancy - roughly doubles your infrastructure costs. It’s like paying for a second apartment that’s the same size as the first, and you’re always paying the same rent for it, month after month, just in case your main place burns down.” She pauses, then adds the part that rarely makes it into the marketing copy. “It’s a rational financial decision until the moment the fire starts.”

Weeks later, once systems were partially restored, Park finally logged in again. He knew the physical frame on his desk was ash - nothing in the affected rooms had survived. But he clung to the digital promise, to the idea that the cloud had already done the saving for him.

He opened his personal G-Drive folder. The file was gone. It had lived in the gap: uploaded on a normal evening into a system treated as a vault, but in practice dependent on a single building and a line item. The dashboards would return to green. The system would be called reliable again. But Park’s proof of that day - his daughter in cap and gown, the signatures of the dead and the living on the back of the frame - had been sacrificed to the efficiency of the whole.

He thought about what “reliable” had meant to him when his monitors were green and the word cloud still sounded like weather. The engineers had built a fortress against the predictable death of machines. They had not built a way around the human reality of the gap.

“The last sliver is where the tragedies live,” the engineer had said. Park had trusted the cloud to be a vault. He had forgotten the detail that matters most: every vault has a budget - and every budget draws a line somewhere. I asked the engineer whether Park’s case was unusual. She paused for a long time before answering. “No,” she said finally. “It’s just the first one anyone told you about.” The system survived. The photo didn’t.

***

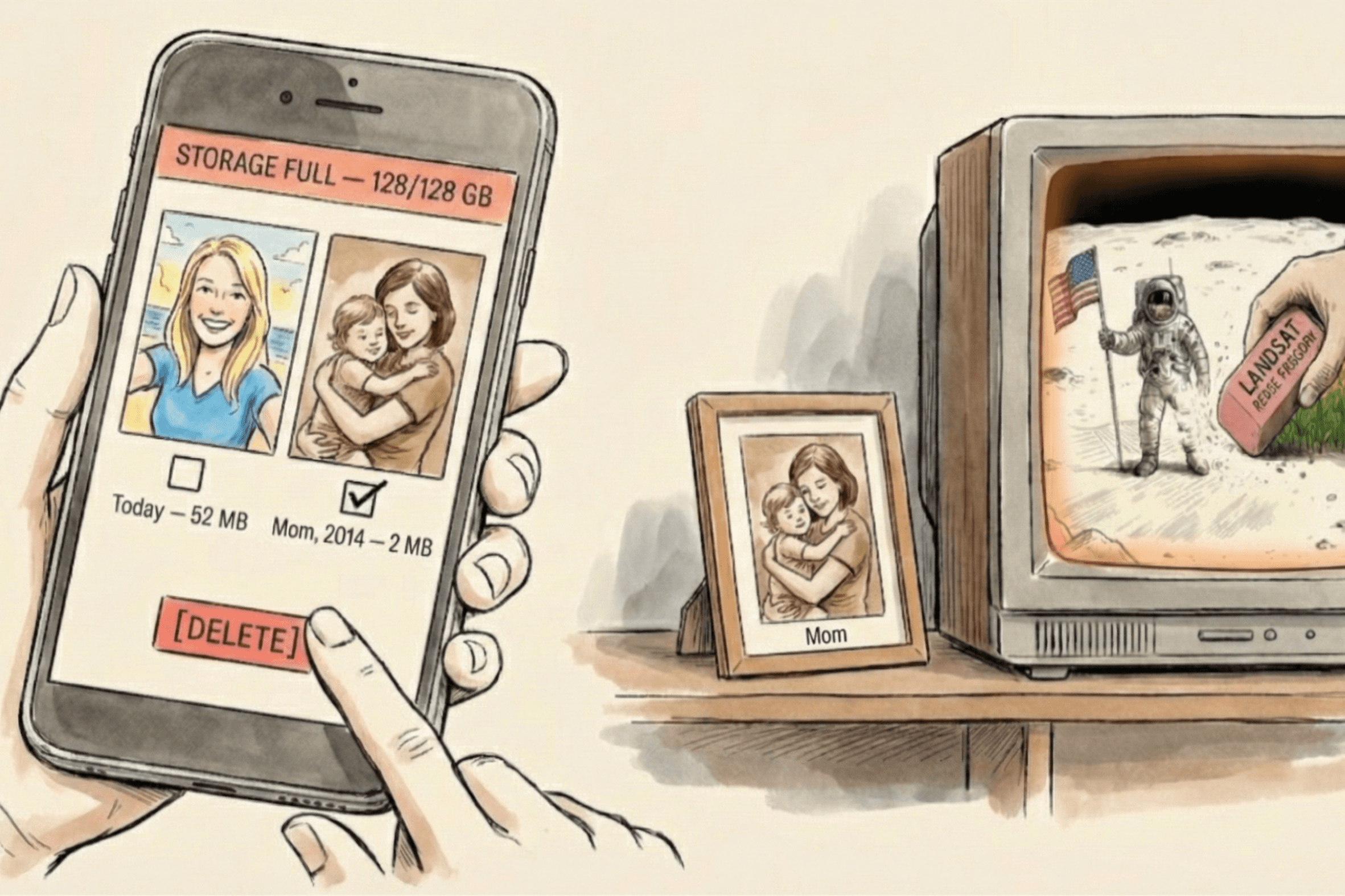

We have seen this kind of erasure before - rarely dramatic, usually dressed up as efficiency. By 2006, Richard Nafzger, a veteran NASA engineer at the Goddard Space Flight Center, had joined a search that would stretch over three years and two continents. He wasn't hunting for anything obscure. He was hunting for the original telemetry tapes containing the raw slow-scan television feed from Apollo 11.

The footage the world watched on July 20, 1969 - Armstrong's ghostly descent, the grainy figure stepping off a ladder - was not what the lunar camera actually produced. The signal beamed from the Moon was incompatible with commercial television. To fix this, the slow-scan signal was converted at tracking stations on Earth into standard broadcast video. What the public saw was a degraded copy - essentially a camera pointed at a monitor. Nafzger wanted the raw signal: the data that existed before the conversion, cleaner and significantly more detailed than the images lodged in the global imagination.

So he and his team did the work that makes archives sound romantic until you've tried it: manifests, handwritten logs, transfer orders, phone calls to retirees who might remember where a specific crate was shipped forty years ago. They followed a trail through storage facilities in the United States and Australia until the paper stopped making sense. To understand why, Nafzger had to rewind not to 1969 but to the early eighties, when NASA faced a problem that was neither heroic nor cinematic.

It needed more tape. The agency was ramping up Landsat, a program built to map the Earth's surface - wheat fields, forests, coastlines, the planet rendered as inventory - and it generated torrents of data. New high-fidelity reels were expensive; supply was strained. Under pressure, managers did what people always do: they looked around for what seemed available.

In storage were shelves of older reels - Apollo-era among them. In the logic of the moment, the moon landing was yesterday's news. The broadcast had been a triumph. The recordings felt like redundant backups of something the world had already seen. So a rational decision followed. In the early eighties, during a one-inch tape shortage driven in part by Landsat demand, tapes were pulled, degaussed - magnetically erased - recertified, and reused to feed new missions.

Nafzger later estimated that the Apollo 11 event alone occupied about forty-five one-inch reels. The history of the moonwalk wasn't lost in a fire. It was overwritten by maps of fields and forests. The Moon was erased to make room for a cornfield.

That July, in the fortieth-anniversary season of Apollo 11, the search team released its conclusion: the raw-feed tapes were almost certainly gone. Nafzger spoke about the loss with resignation, not anger. He understood the logic of the time. Tape was scarce. The data seemed redundant. What unsettled him was how reasonable it had felt when it happened. We don't usually wipe history in a fit of passion. We wipe it to keep things moving, to clear space, to satisfy a constraint.

It is also the failure mode Vinton Cerf - one of the architects of the internet - has warned about: a “Digital Dark Age,” not because we burn libraries, but because we lose the ability to read what we saved. Paper is self-describing: a letter pulled from a trunk can still announce itself as language. A historian can still decipher a torn manuscript from the twelfth century. Digital artifacts are not. Strip away the software, formats, and context that make sense of the bytes, and the record can survive intact while becoming indistinguishable from noise. “We may not know what it is,” Cerf warns.

NASA's managers assumed they had preserved what mattered. They didn't know what they were erasing until decades later, when someone asked for the original again. That is the part people misunderstand about "data loss." We imagine catastrophe: fire, flood, a hacker. But a great deal of damage is administrative. It comes from housekeeping - making room, cutting costs, migrating systems, deprecating formats, deleting what seems redundant because the copy exists somewhere else.

The locks in this story - servers shut down, accounts disabled, verification codes trapped on a melting phone, backup windows a budget didn't buy - look like interruptions. The overwrite is quieter. It is what happens when nobody is malicious and everyone is being sensible. Housekeeping has no sense of drama. It doesn't care whether you are deleting the Moon or deleting a folder called "2014".

If an agency defined by foresight could erase the Moon to save tape and shelf space, what chance does a mother have against the pragmatic urge to clear her phone? She doesn't want to erase history. She's trapped in a hardware paradox: the quality of her life's record has outpaced the container built to hold it. Her camera captures 4K video that devours gigabytes in minutes, while her phone still comes with 128 gigabytes. Faced with "Storage Full," she makes the same rational decision NASA made. She deletes the old to make room for the new.

***

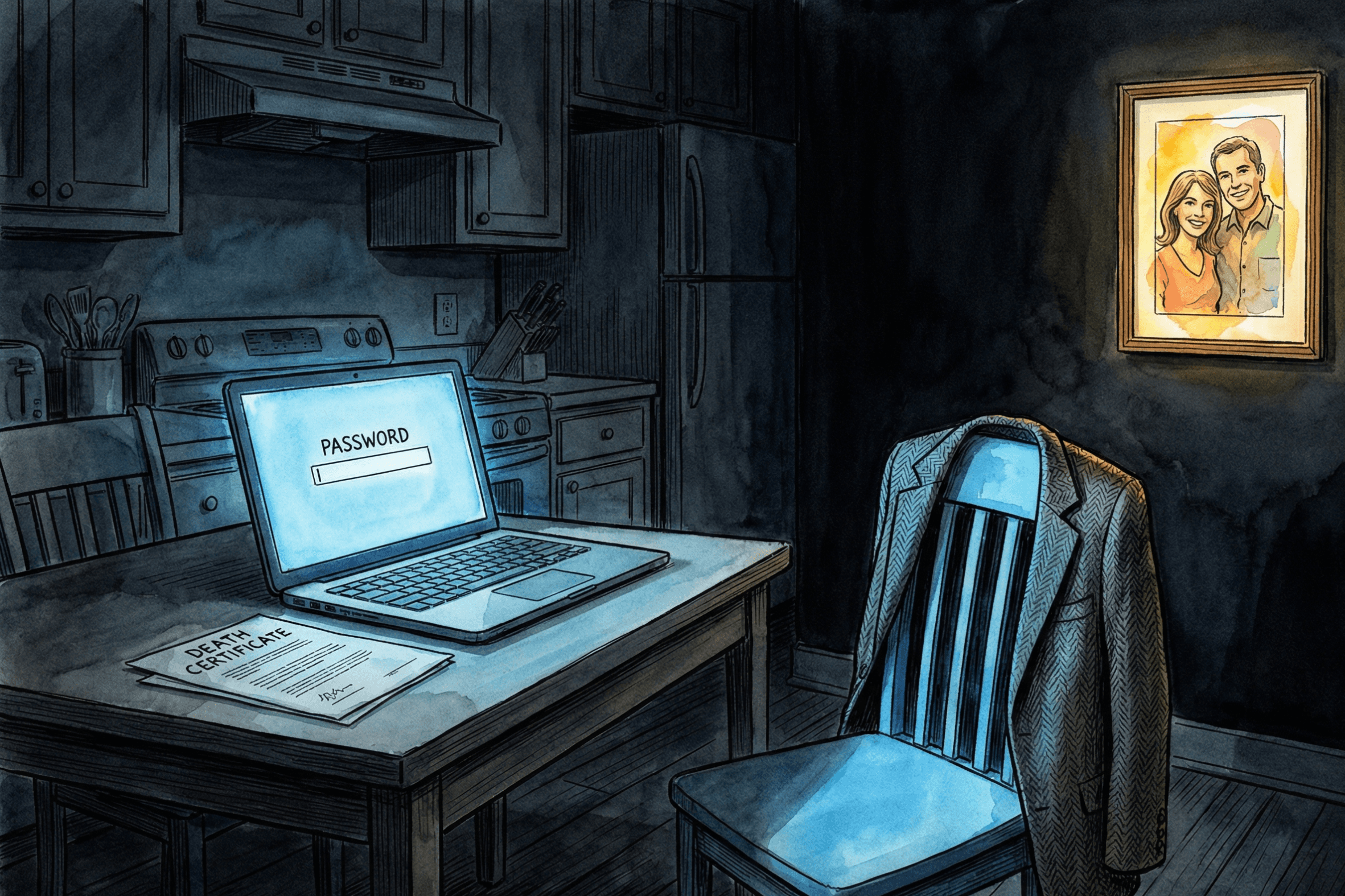

Richard Nafzger watched history vanish because someone needed empty shelves. Elizabeth, a widow in her late fifties in Portland, Oregon, lost the past because it was locked.

Her husband, Michael, died on a rainy Tuesday in February. After the funeral - after the casseroles stopped arriving and the house settled into a profound silence - Elizabeth began the grim administrative work of untangling a shared life. She called the bank, the mortgage company, and the credit-card issuers. It was difficult, but straightforward - governed by centuries of probate law and the reassuring principle that death transfers ownership.

Then she tried to access his email. Elizabeth sat at the kitchen table staring at her laptop. It was the same table where Michael used to answer emails while she cooked dinner. Now the screen showed a password prompt she could not get past. The question was simple. The answer died with him.

Michael had been the family archivist. His account held the digital breadcrumbs of their nearly twenty-five years together: a folder of PDF tax returns; an email thread with an Army buddy named "Dutch," debating their2004 deployment; confirmations for a trip to Kyoto they'd been planning for their silver wedding anniversary - one they would never take.

Elizabeth needed access to settle his affairs. But the need that kept her at the table wasn't only financial. She wanted, as she put it later, "the texture of his mind." So she did what the modern world trains you to do. She asked for help. She submitted a request to the provider, attaching a scanned copy of the death certificate. The rejection arrived three days later - polite, firm. The support agent cited the company's privacy policy and a strict reading of the federal Stored Communications Act. Without a court order - and, depending on the judge, perhaps even with one - the account would remain sealed.

To the bereaved, the refusal feels like bureaucratic cruelty. You have the death certificate. You have the wedding ring. You have the keys to the house. And yet the one place where modern life keeps its inner voice - the inbox, the drafts, the search history - remains behind glass.

"It sounds... well, cynical, I get that," says Alex, stirring sugar into a coffee that has long since gone cold. He is sitting in a café in Menlo Park, fresh from the Andreessen Horowitz complex, where he spent the morning pitching a startup built around data privacy safeguards for the AI era. The adrenaline of Sand Hill Road is still vibrating in him; every thirty seconds, his eyes dart down to the notifications pulsing on his wrist, checking for a verdict from the very system he claims to control.

"To deny a widow - that’s villain stuff, right? But look: if we give her access, the whole model collapses. Totally collapses." He glances at his watch again, a reflex he doesn't seem to notice, before leaning in. "A dead man's account isn't just an archive," he continues, lowering his voice. "It’s... listen, it’s their 'shadow self.' It’s the incognito searches. The weird forums. We are basically guarding the things the person kept silent about. If we open that door just for the sake of empathy, we violate the dead person’s most important right: the right to remain who they pretended to be."

Alex calls it the "Digital Diary" dilemma. A shoebox of letters found in an attic is curated by accident; it is partial, even polite. A cloud account is different. It can hold a near-complete, unedited record of a person's inner life - search histories, private confessions, perhaps a struggle with addiction, perhaps a confidential conversation the deceased never intended to share. "Especially to a spouse," Alex adds quietly.

"We become, by default, the executors of a silence the user can no longer enforce," he says. "When we deny a widow access, we aren't just protecting the company from liability. We are protecting the dead man's right to be known only as he chose to be known."

It is a coherent moral position. To Elizabeth, it felt like theft. The logic of probate law - where assets pass to the living - did not reach the cloud. The cloud had its own probate, one that began not with a death certificate but with authentication. Michael wasn't a husband whose estate needed settling; he was a user who had stopped logging in, and whose privacy settings were treated as his final will and testament.

Elizabeth tried again. And again. Each time she had to explain Michael's death to a stranger, in a format designed for tickets, not mourning. Eventually, she stopped - not because she accepted the logic, but because the emotional toll became too high. She closed the laptop. The photos were there - thousands of them, including a blurry shot of a rental car in 2008 that made them both laugh. Physically, they were likely sitting on a hard drive in a data center just up the Columbia River, less than eighty miles from the table where she sat. Michael's emails, his travel plans, his digital footprints: all intact, all unreachable. She had inherited his house, his car, his wedding ring. But she couldn't inherit their digital archive of memories, which they had painstakingly accumulated over 25 years.

Some platforms have begun to treat "death transfers ownership" not as philosophy, but as a product requirement. Apple, for example, lets users designate a Legacy Contact who can request access after death. The checkbox exists. So does the catch: it only works if it was set up in advance, and even then it does not unlock everything. Michael hadn't left Elizabeth a plan. Most people don't.

Elizabeth could not be reached for comment. Friends recall that, years later, someone close to her asked if she wanted to take down Michael’s photo from the mantelpiece. “No,” Elizabeth is said to have replied. The photo was hers - tangible, fading slightly from sun exposure, but stubbornly there. Unlike his emails. Unlike his digital archive. Unlike nearly twenty-five years of correspondence locked behind a password she would never retrieve. “The photo, at least, I could hold.”

***

What startled Étienne most wasn't the loss of The Crew. It was how quickly the loss began to resemble other stories - different surfaces, the same mechanism underneath. The failures in these pages do not belong to separate categories of misfortune. They belong to one system: memory unbundled into accounts, vendors, formats, devices, authentication, billing, and policy and then sold back to us as if it were seamless.

For centuries, family memory was hard to destroy by accident. It lived in thick albums, shoeboxes, drawers, closets, and the tin boxes that once held Christmas cookies. It could burn. It could flood. But it did not vanish because someone in another city changed a retention rule, or because a verification code went to a phone you no longer had. Its vulnerabilities were physical. You could name them.

Digital memory is different. It is astonishingly durable and astonishingly fragile at once. It can be duplicated across continents, yet undone by small, quiet failures: a lapsed subscription, an expired card, a lost device, a policy change, a backup that lagged behind reality by a few minutes. It can be "backed up" and still slip through the interval between "uploaded" and "durably copied."

There is an old Alexandrian story that captures the opposite instinct. In the third century B.C., Egypt's rulers, the Ptolemies, wanted to build a universal library - a warehouse for the world's mind. To fill the shelves, they turned the city's harbor into a checkpoint for knowledge. Galen writes that books found on ships entering the port were seized, copied by royal scribes, and the copies were returned. But the library kept the originals, labeling them "from the ships."

When Ptolemy III decided he needed Athens' official master texts of the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, he managed to borrow them against a massive deposit: fifteen talents of silver. Fifteen talents was not pocket change. An Attic talent of silver has been estimated at roughly nine person-years of skilled work; fifteen talents is a lifetime measured in wages - something like twenty million dollars in modern purchasing power. Yet once Ptolemy held the scrolls, he forfeited the fortune. He sent Athens fine copies and kept the originals.

The point was not the text alone. It was authority: the ancient certainty that the original mattered more than the cost. NASA, two millennia later, did the inverse. It possessed a kind of master recording - the raw Apollo 11 slow-scan television feed - and, during a tape shortage in the early 1980s, the recordings were likely degaussed, recertified, and reused. The world kept the converted broadcast; the raw signal - the closest thing to the original - was treated as surplus.

Étienne's predicament is what happens when you live after both stories: after the age that worshipped originals, and the age that learned to treat them as expendable.

When a problem is widespread and technically messy, a market forms around it. Preservation stops being a hobby and starts becoming an industry. We can already see the shape: estate lawyers drafting "digital wills," legacy-planning checklists, consultants selling "family archive" setups, services that don't really sell storage so much as continuity - an audit, a tested recovery plan, and the guarantee of human help. They step in the moment the system stops recognizing you. The complexity is the product. The choice, eventually, is simple: outsource the complexity or inherit the labor. Etienne had chosen work, for now.

"Now I feel like Ptolemy," Étienne says with a faint smile, gesturing toward the humming tower of drives in his closet. "I keep the originals." He has adopted the "3-2-1" rule - three copies of everything, on two different kinds of media, with one copy kept off-site.

He knows it in his fingers now. On Sundays he does what the cloud never advertises: checks drive health, verifies backups, tests restore procedures, rotates passwords, prints recovery codes, makes sure yesterday's "safe" is still readable today. “Sometimes I try the oldest files on purpose,” he says. “If they don’t open, the archive is already half gone. A Word document from 1998 can sit on a drive for decades and still turn into noise if nothing can read it. That’s my way of fighting back against the Digital Dark Age - at least for my own archive.”

When he finishes, he closes the dashboard and listens to the hum behind the closet door - steady, warm, faintly mechanical. Above his monitor sits a photograph of his parents. It hasn't asked for an update in twenty years. It consumes no electricity. It simply exists. The drive does not simply exist. It demands care. That is the trade the cloud rarely states plainly: convenience moved the work out of sight, not out of existence. And the math - the little percentages that are supposed to make you relax - only irritates him now.

"This 0.01 percent of so-called statistical loss," he says, tasting the phrase the way you taste bad coffee. "I was already in the 0.001 percent - just by being one of the few people in the world who played The Crew. And now you're telling me I have to be in the 0.01 percent who loses their memories? Their identity?" The more common failures are mundane: locked accounts, dead phones, missing recovery keys, format churn, policy changes, subscriptions that lapse, services that merge or disappear. The risk is not one catastrophe. It's the stack - group of locks.

In the deepening twilight of Lyon, the lights on Étienne's drive blink in nervous staccato. It is a noisy, imperfect machine fighting against the silence. It generates heat. It takes up space. It is the burden the cloud promised he could leave behind. He places his hand on the warm plastic casing, feeling the vibration of seven thousand revolutions a minute. "It's work," he says to the empty room. "But it's the only way to keep it."